A Thousand Heroes

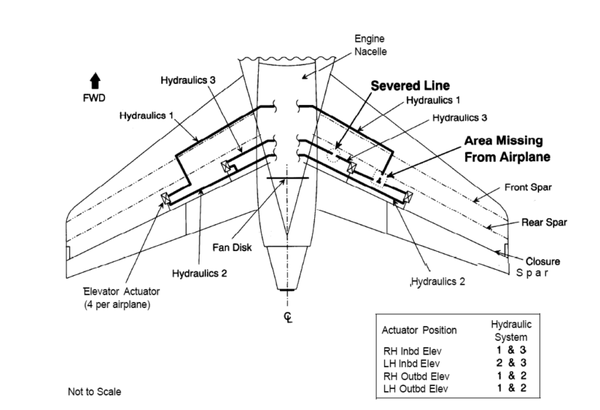

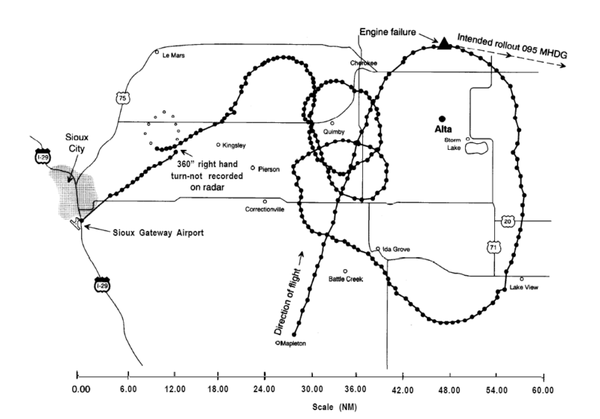

聯合航空232號班機(UA/UAL232)是聯合航空的定期班機。在1989年7月19日,飛行此班次的道格拉斯DC-10-10三引擎客機之二號引擎(位於尾翼基部)因為扇葉片製造的瑕疵,運轉時葉片脫離損壞了機上所有的三套液壓系統,導致各翼面的控制功能失效。在無舵面工作的情況下,機組人員在原本坐在後艙中的一位非值勤飛行員之協力下,靠著控制僅存的2具引擎調整飛行方向,嘗試讓班機在愛荷華州蘇城(Sioux City,Iowa)緊急迫降,而常被稱為蘇城空難。雖然在迫降時還是不幸發生機身翻覆的情況,造成285名乘客中有110人喪生,11名乘務人員中有1人喪生的悲劇,但若不是機組人員的拯救得當,原本傷亡應更加慘重。由於當時地面上的人員早就知道該班機可能會在迫降時失事,因此電視台攝影師早已在機場邊等候記錄飛機迫降的過程,使得它成為航空史上記錄最完整的空難之一。

在本次事件中,生還者之一的機長艾爾·海恩斯(Al Haynes)在後來2003年到比利時布魯塞爾參加一場航空安全相關的研討會,參加研討會當中的一位機長就是2003年DHL貨機巴格達遇襲事件中的DHL貨機機長艾瑞克·甘諾特(Eric Gennotte,比利時人),這個戲劇性的巧合讓該事件得以化險為夷,進而成為世界首宗大型航機在無液壓控制的情況下,通過控制引擎的出力大小以達到調整飛行姿態的方式安然降落的案例。

道格拉斯DC-10是道格拉斯公司應美國航空要求而研製的飛機,原為雙引擎客機,後為確保可在短跑道上起飛及因應美國航空的要求而加上第三引擎。DC-10於1989年停產,共生產446架(包括60架交付美國空軍的KC-10A軍用版)

DC-10啟用後數年,業界開始發現這型號飛機在設計上有相當的缺陷,其中較嚴重的是機腹貨艙艙門設計,引致多次空難導致麥道需要對貨艙艙門進行重新設計。在1979年,DC-10更在一年內涉及三宗意外,雖然意外起因與飛機本身設計並無直接關係,但當時航空當局以安全理由,要求全球的DC-10停飛,損害了DC-10飛機的名聲。其後的聯合航空232號班機空難雖然後來被証實與道格拉斯無關(因通用電氣製造的引擎缺陷),但也令DC-10飛機的名聲進一步受打擊。

涉及DC-10的空難事故

自1972年以來,DC-10牽涉於很多重大空難事件中,以下是一些較重大的事故:

- 1972年6月12日,美國航空96號班機由底特律飛往水牛城途中,因機尾貨艙門設計缺陷,以致在爬升途中突然打開,導致爆炸性失壓,飛機最後能返回底特律機場緊急降落,無人死亡。

- 1974年3月3日,土耳其航空981號班機由法國巴黎飛往英國倫敦途中,遇上和美國航空96號班機一樣的情況,但這次爆炸性失壓將所有液壓管道扯斷導致無法操控,飛機在巴黎郊區墜毀,機上346人死亡。

- 1979年5月25日,美國航空191號班機在芝加哥奧黑爾國際機場起飛後不久墜毀,機上273人和地面2人死亡,事後調查指美航維修人員沒有依正常維修程序去維修引擎導致意外。

- 1979年10月31日,美國西方航空2605號班機(Western Airlines)於降落墨西哥城時,錯誤地降落在一條封閉的跑道上,與跑道上的地勤車相撞,結果造成73人死亡,包括地面一人。

- 1979年11月28日,紐西蘭航空901號班機在進行定期的南極洲觀光航班時,在埃里伯斯火山山腰墜毀,機上257人死亡。事後官方調查指出機長把飛機下降至低於飛行安全條例規定的下限導致意外。但紐西蘭法官彼得·馬翰於1981年發表的另一份調查報告指責紐西蘭航空在沒有通知機組人員的情況下,單方面修改航程飛行計劃,亦同時責空中交通管制員容許901號班機下降至低於飛行安全條例規定的高度。

- 1982年9月13日,西班達斯航空995號班機(Spantax)於馬拉加機場起飛時因機件故障導致起飛失敗衝出跑道,飛機爆炸起火,全機393人中,50人死亡。

- 1989年7月19日,聯合航空232號班機因二號引擎扇葉片脫落損壞了機上所有液壓系統,導致飛機無法正常控制,飛機嘗試在愛荷華州蘇城緊急降落時,發生機身翻覆的情況,285名乘客中有111人死亡。這事件被稱為「蘇城空難」。

- 1989年7月27日,大韓航空803號班機於濃霧下降落利比亞的黎波里機場時失事,於跑道附近墜毀並波及路上車輛,結果造成地面4人死亡[5](另有說法指6人[6]),飛機本身亦有75人死亡。

- 1989年9月19日,法國聯合航空772號班機(UTA)於尼日一個沙漠上空發生炸彈爆炸,全機171人死亡。

- 1992年12月21日,荷蘭馬丁航空495號班機於葡萄牙法魯降落時遇上微下擊暴流墜毀,機上340人中56人喪生。

- 1996年6月13日,印尼加魯達航空865號班機於日本福岡起飛失敗,從半空中摔回地面爆炸起火,3人死亡。

- 1999年12月21日,古巴航空261號班機為一架向法國AOM航空租用的26年機齡DC-10-30型,於瓜地馬拉市降落時衝出跑道,機頭撞向民居,機上17人及地面9人死亡。

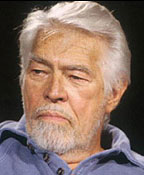

機長 Al Haynes

One of the most famous pieces of video tape history shows the crash landing of United Airlines flight 232 in Sioux City, Iowa.

Captain Al Haynes remembers...

"I asked if everybody made it. And Dudley said no. And I said Oh my God, I killed people," said Haynes.

Haynes was knocked out by the impact, in and out of consciousness as he was pulled from the wreckage. But Haynes and his crew would become heroes, because what happened that day still stands as one of the most remarkable pieces of airmanship in aviation history; trying to land a plane he could barely control.

"It happened. I've learned to accept the fact that it happened. I feel terrible for the people who didn't make it, and the families. But we did everything we could do and there wasn't anything we could do about it," said Haynes.

Related Content

One-hundred-11 people died, but 185 survived. Haynes beat the odds.

"The odds are, it's a billion to one of losing it," he said.

Some of the heroes that day were in the tower.

"I couldn't even fathom until they came on, that I realized that basically they were out of control," said air traffic controller Kevin Bachman, who now lives in Seattle. "For the entire time, I knew a crash was a possibility."

Flight 232 was heading from Denver to Chicago. DC-10s have three separate hydraulic systems to control the plane, but when part of the center engine cracked and exploded, the hydraulics were rendered useless.

"We had no ailerons. We had no rudder. We had no elevator. We had no spoilers. We had no wing flaps. Everything that controlled the movement of the airplane we lost," said Haynes.

It was time to improvise, and that came from the plane's engines. Haynes and his fellow pilots made it all work.

"These two engines, and by varying the thrust on those two engines, we could skid the airplane one way or the other. And if you thrust both throttles up at the same time, the increase in thrust would pitch the nose up, and if you closed both throttles it would pitch the nose down," he said.

After nearly 45 minutes it looked like the crew would be able to land.

"It looked real good. I thought he was going to make it," said Bachman.

But then the right wing touched the ground.

Haynes said the first time he saw the famous video was three days after the crash.

"I saw it on TV. I couldn't believe it was us," he said.

"And when it hit, and it rolled over. And you think everybody's dead, it just ripped your heart out," said Bachman.

For Al Haynes, talking about the accident is therapy, from the time he was recovering in the hospital to the time two years later, back as a DC 10 captain, when it was time to retire. He never flew as a pilot again.

"We put our resources and knowledge together and did what we thought was best," he said. "If you're going to call a hero, you've got to call everyone involved. The hundreds or thousands involved in the whole operation.

The Sioux City airport was the biggest airport Haynes and his crew could go for, and became the stage for the investigation into the cause. But the passengers had other things going for them.

"Two hospitals right there, right at shift change. You had a lot of people. You had the National Guard at the airport. You had a flight crew who had a training pilot sitting in back who could help out. It was just a miracle what happened," said Bachman.

It could have been, so much worse. And to this day, Al Haynes is on the lecture circuit sharing his knowledge about teamwork in tough conditions.

"Everybody grieves in their own way. But I think to get back into what you're doing as quickly as you can is the best thing you can do. But that's for me. Doesn't work for everybody," he said.

Haynes and his crew are part of an exclusive club, recently joined by Captain Sullenberger, who successfully landed an Airbus on the Hudson River in January. The two men have become friends, pilots who've been ready and come through against terrible odds.

Al Haynes continues to speak to groups about the crash and the importance of teamwork.

The National Transportation Safety Board's findings led to changes in the way airlines inspect engines, and make it much harder for a plane to completely lose its controls.

機長 Al Haynes

Beyond survival

Life's trials continued for pilot after 1989 crash

By Ann Carnahan, Rocky Mountain News

May 7, 2005

Al Haynes is alone now, except for a daughter, a son and the United Airlines passengers who credit him with saving their lives.

The veteran pilot was at the helm July 19, 1989, when he and his crew crash-landed a crippled airliner in an Iowa cornfield. More than half of the passengers survived.

Rodolfo Gonzalez © News

Capt. Al Haynes, who piloted the United Airlines flight that crashed in Sioux City, Iowa, on July 19, 1989, speaks at the United Airlines Flight Training Center in Denver. Haynes was hailed as a hero when 184 of the 296 passengers and crew survived a crash that many said should have killed everyone on board.

Flight 232 had taken off from Denver that afternoon with 296 passengers and crew on board when an explosion in its rear engine severed all of its hydraulic lines. The pilots couldn't control the plane, which wobbled perilously for 42 minutes. It was, experts said, a miracle anyone survived. Haynes was widely regarded as a hero because he found a way to bring the plane down nearly level with the ground. Then-President George H.W. Bush praised his performance. Charleton Heston played him in a TV movie.

Now 73, Haynes lives in Seattle and still gets together for occasional barbecues with the flight's crew. They have a special bond, he said.

He has developed close friendships with five or six of the passengers, and even though nearly 16 years have elapsed, he still gets a couple of dozen Christmas cards every year from survivors.

But the man who helped save 184 lives that day has suffered great personal loss.

In 1997, his oldest son, Tony, died in a motorcycle crash. Two years later, his wife of 40 years, Darlene, developed a rare infection after suffering a ruptured colon. She died the day before the 10th anniversary of the crash in Sioux City.

Haynes nearly suffered another loss three years ago when his daughter, Laurie Haynes Arguello, was diagnosed with aplastic anemia, a rare disease that renders bone marrow unable to make new blood cells.

She needed a bone marrow transplant but didn't have the $256,000 necessary for the procedure, which was not fully covered by insurance. Follow-up care would run in the tens of thousands of dollars.

And then another miracle of sorts happened.

Hundreds of people rallied around Haynes to help him save one more life.

After he sent out a letter to family and friends asking for their help, they opened their wallets. Many donations came from crash survivors. Even family and friends of some of the 112 who died made contributions.

In all, $550,000 was raised. The National Foundation for Transplants oversees the money, which will cover Arguello's transplant-related expenses for the rest of her life.

On April 15 of last year, Arguello, who has a young son, underwent the transplant and came through with flying colors.

"She just didn't show any signs of problems at all," Haynes said. "But it can happen at any time. Now, at 40 years old or 60 years old or whatever, she could have a reaction of some sort. But right now, she's had absolutely none."

A couple of months ago, Arguello wrote a letter to the man who donated his bone marrow. All she knows about him is that he is 27 years old. She sent her letter to the Seattle cancer center that treated her, and it was forwarded to him.

Someday, Haynes said, it's possible his daughter will meet the man who saved her.

Recounting the crash

Haynes travels all over the country, talking about the crash.

"It's therapy for me," he said. "I feel it's something I need to do."

He's given 1,500 speeches to roughly 330,000 people about the role teamwork played in limiting the death toll.

Sometimes he speaks to corporate managers, emphasizing that they can run their businesses the same way the pilots ran their cockpit that day. Even the most junior employees, he says, have knowledge or training, or they wouldn't be working for you.

Haynes doesn't charge a fee, but he asks the groups to donate money to scholarships in memory of those who died on the flight. So far, Haynes' talks have raised about $1 million.

Earlier this year, Haynes spoke at the United Flight Training Center near the old Stapleton Airport in Denver.

He began his presentation with a video that included chilling radio transmissions between Flight 232 pilots and air traffic controllers. The video also paid tribute to hundreds of National Guardsmen, doctors, nurses and rescue workers in Sioux City.

Five things came together to keep the death toll down, Haynes said: luck, communication, preparation, execution and cooperation.

The Chicago-bound DC-10 took off from Stapleton that afternoon, cruising along uneventfully for nearly an hour and a half.

Then, at 37,000 feet, somewhere over northwestern Iowa, a loud pop rocked the tail of the turbo jet. The plane shuddered and lurched, then dropped several hundred feet.

In the cockpit, Haynes heard the explosion, but he wasn't particularly alarmed. The plane could still fly smoothly with just two engines.

'I can't control the plane'

Within a few minutes, however, Haynes, flight engineer Dudley Dvorak and first officer Bill Records, who was flying the plane when the engine exploded, noticed disturbing changes in the flight panel. A warning light flashed, signaling trouble in the jet's hydraulic systems. Gauges displayed a steady drop in fluid pressure.

Then, Haynes said, "Bill gave the attention-getting statement of the day: 'I can't control the airplane.' "

Haynes said he then grabbed the control wheel and said "the dumbest thing I've ever said: 'I got it Bill.' I realized right away I couldn't control it either."

By then, the plane was descending at 1,000 feet per minute. The crew could turn the plane to the right, but not the left.

At some point, passenger Denny Fitch, an off-duty United pilot and trainer, made his way to the cockpit and offered his help. Together the four men brainstormed for a way to land the plane successfully under a scenario considered so rare and hopeless that pilots didn't train for it. They thumbed through flight manuals but came up empty. Twice, they called United's maintenance center in San Francisco for ideas, but nothing.

So they made it up as they went along. They nosed the plane down by varying and gradually adjusting the engine power. They constantly adjusted the thrusters, adding power to the right engine and reducing it on the other side so they could nudge the jet left.

They talked with air traffic controllers, who suggested landing in Des Moines. Haynes asked for a closer airport and aimed for nearby Sioux City.

With the flight just 20 miles from the airport, Haynes told the controller:

"Whatever you do, keep us away from the city."

Controllers told Haynes he could land on an interstate east of the airport. Haynes responded that he was going to try for the airport. The controller said all runways were available and that emergency equipment was ready.

A few minutes before impact, Haynes calmly told the passengers to prepare for an emergency landing. "I don't want to kid you, but it's going to be rough," he told them.

The plane, operating without brakes, landed nearly level with the ground. At the last minute, the right wing dipped slightly and hit first. The impact left an 18-inch deep hole in the concrete as the plane broke apart and burst into flames.

Even so, the landing was considered remarkable under the circumstances. Simulator tests conducted after the crash showed that other DC-10 crews were unable to repeat the efforts of the Flight 232 crew.

Teamwork won the day

Haynes credited luck: The weather was good, emergency crews in Sioux City had trained for a wide-body jet crash, the Iowa National Guard was meeting in Sioux City that day and the crash occurred during shift change at the town's two hospitals, effectively doubling the staff.

He also acknowledged the teamwork of the men in the cockpit. In the past, flight crews simply did what the captain instructed, Haynes said, reluctant to offer opinions or suggestions.

"If the captain made a mistake, well that's too bad," Haynes said. "Well, now that's not the way it's done anymore. The whole crew contributes.

"The day of 'I will solve the problem' is over. Now, it's, 'We will solve the problem.' "

Haynes said he never has nightmares from the crash. He was knocked unconscious on impact and so "I didn't go through the crash."

He suffered a head injury that left him with a concussion and 92 stitches. He also suffered a cut ankle and bruised rib and sternum. His left ear was nearly cut off.

Haynes spent five days in the hospital, where he also underwent intense counseling.

"I was devastated," he said. "I was always wondering and fighting, 'Why didn't all 296 survive?'. . . Over time, I see we were extremely fortunate. My question is, 'How did 184 survive?' It should have been a non-survivable crash."

Haynes suffered survivor's guilt and, in a small way, still does.

"It's always there," he said. "You just have to deal with it, accept it and go on."

Seated in the front row at the training center, hanging on Haynes' every word, are two passengers from Flight 232, Jerry Schemmel and Garry Priest.

Enduring friendships

Schemmel, a Denver Nuggets radio broadcaster, and Priest, a custom home builder and country western singer, didn't know each other before the crash.

Today, they're friends.

Both men also consider Haynes a close friend, though he is old enough to be their father. They've shared many dinners, usually meeting when Haynes is speaking in Denver. They talk about the crash, how they felt and the aftermath on the ground.

Schemmel, who contributed to the transplant fund for the pilot's daughter, said he is even more impressed with the man Haynes has become since the crash than the man he was in the cockpit that day.

"He always has the time for anyone connected with the crash, and I think it could have gone the opposite way," Schemmel said. "He could have gone into a shell and said, 'No, leave me alone. I have to deal with myself.' But he's done the opposite. He's attacked it, almost, and faced it head-on, and I like that approach."

Also in the audience was Susan Callendar, a flight attendant on the stricken airliner. Like Priest and Schemmel, she gets together with Haynes about once every year when he's in Denver. When she got married two years after the crash, Haynes came to her wedding.

"Al is my hero," said Callendar, who still flies for United and thinks about the crash everyday.

A survival crash

In his talks, Haynes tells people to always be willing to listen to someone experiencing post- traumatic stress syndrome.

He returned to work three months after the accident and wasn't nervous at the controls, he said. In 1991, Haynes retired and has never flown a plane of any kind since. He doesn't miss it, he said, because he's too busy.

He umpires Little League games in Seattle and does play- by-play for high school football games.

In the past few years, Haynes has cut back his speaking engagements from 100 per year to about 60, which is still enough, he said, to provide him therapeutic benefits.

The Flight 232 crash became a "survival crash" in the media, Haynes said, but that offered little solace to the families of the 112 who died. Hayes said that he's never forgotten those who didn't make it and that his talks are dedicated to them.

"The only thing that concerns me about that whole crash is that we weren't able to save everybody," he said. "And that's the bottom line. That's all I ever think about."

He said he'll always remember how calm the passengers were, even when he explained the gravity of the situation.

"I will stand in awe of them," he said, "for the rest of my life."

Survival crashes

136 survived the crash of American Airlines Flight 1420 in 1999 bound for Little Rock , Ark., from Dallas and carrying 145 passengers and crew.

189 survived the crash of United Airlines Flight 173 in 1978 bound for Portland, Ore., from Denver and carrying 199 passengers and crew.

The perilous journey of United Flight 232

Bound for Chicago from Denver, United Airlines Flight 232 wobbled for 42 minutes as the cockpit crew struggled to control the plane before crash landing in Iowa on July 19, 1989.

Jerry Schemmel a Denver Nuggets broadcaster and a passenger on the fllight, has stayed in contact with Haynes.

Capt. Al Haynes, who, piloted the ill-fated United Airlines Flight 232 in 1989.

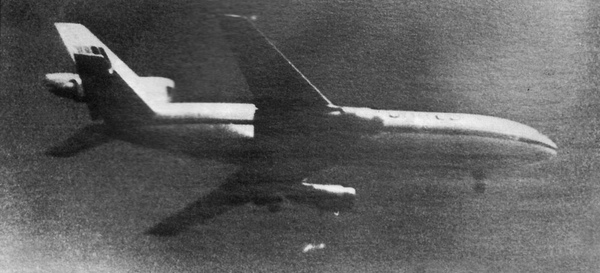

Flight 232 is seen just seconds before impact at Sioux City Gateway Airport. About an hour and a half after takeoff, at 37,000 feet, a loud pop rocked the jet's tail. The plane shuddered, lurched then dropped for several hundred feet. The pilot, flight engineer, first officer and an off-duty pilot on board worked together to bring the plane down. That 184 of the 296 passengers and crew on board survived was hailed by many as a miracle.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cU2mqOLzlfU 蘇城空難

The images are familiar: the video shot through a chainlink fence of a jetliner engulfed in flames cartwheeling down the runway at Sioux City, Iowa. The cause of the disaster was the catastrophic failure of the fan disk on the airliner's tail-mounted engine. The engine assembly did not contain the debris, and all three of the airplane's redundant hydraulic lines were severed, sending the plane's entire hydraulic system into the weeds. Without any hydraulics, none of a plane's control surfaces will work, pretty much making the plane impossible to fly.

Spencer Bailey, a young survivor, being carried to safety by Lt. Colonel Dennis Nielsen after the crash

Since the hydraulic lines were triply redundant, this was one of those failures that had been considered impossible by the aircraft's manufacturer and engineers, and was not trained for in any flight simulators. The crew quickly realized that they had virtually no control over the plane, and their only method of steering and maintaining altitude was by clever manipulation of the remaining engines' thrusts independently. At one point during the flight, a man by the name of Dennis Fitch offered his assistance to the flight crew. It just so happens that he was a DC-10 instructor and pilot who was deadheading as a passenger on the plane. He was able to offer much assistance in working the throttles to maintain control of the aircraft.

The CVR transcript from the flight is a must-read, and really completes the story. Some of my favorite excerpts follow:

[When Capt. Fitch enters the cockpit]

Captain Haynes: My name's Al Haynes.

Captain Fitch: Hi, Al. Denny Fitch.

Captain Haynes: How do you do, Denny?

Captain Fitch: I'll tell you what. We'll have a beer when this is

all done.

Captain Haynes: Well, I don't drink, but I'll sure as hell have

one. Little right turns, little right turns.

[Approaching for the crash landing]

Sioux City Approach: United two thirty-two heavy, the wind's

currently at three six zero at one one three

sixty at eleven. You're cleared to land on

any runway...

Captain Haynes: [Laughter] Roger. [Laughter] You want to be

particular and make it a runway, huh?

Fitch and the crew were able to maneuver the plane just enough to get it to the runway, and actually touch down near the end, and on the center line. Unfortunately, due to the high airspeed and sink rate of the plane, a wing touched the ground and sent the plane into a somersault, breaking up the aircraft. It is believed that just getting the plane on the ground on the runway is what saved the 185 survivors of the crash (including the crew). An interesting footnote to the story, which I discovered in the Wikipedia article , is that Michael Matz, a passenger on the plane considered a hero for helping to pull children out of the flaming wreck, trained this year's Kentucky Derby winner Barbaro.

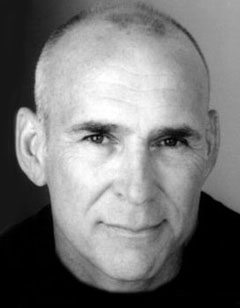

Denny Fitch

Denny Fitch

|

|

On July 19, 1989, Captain Fitch was a passenger on United Airlines Flight 232. He was simply returning home after a week at his job as a pilot trainer in Denver, enjoying the ride at 37,000 feet. That was until a catastrophic failure in one of the engines cut all hydraulic controls in the plane - a problem so unthinkable that there was no procedure for dealing with it. Denny Fitch then volunteered his assistance to the cockpit, and with Captain Al Haynes and the rest of the flight crew, guided the plane to Sioux City, Iowa under the most trying of circumstances. While 112 souls perished in the terrifying crash landing, 184 people survived because of the incredible teamwork and leadership of the men in the cockpit and the control tower. Without the use of any of the systems required to control the plane, Captain Denny Fitch and his colleagues missed being completely successful by only a matter of inches. He and the crew hold the distinguished record of the longest time aloft without flight controls who lived to tell about it. Captain Fitch was commended by President George Bush and in Senate Resolution 174 of the 101st Congress for his outstanding effort, poise and courage in assisting the crew in attempting a difficult emergency landing at Sioux City, Iowa. He is a safety consultant to NASA as a member of the Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel and Captain Fitch has also been inducted into the Aviation Hall of Fame at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Denny Fitch has given numerous inspirational and motivational presentations to various corporate and association groups. In his discussions, he uses his own incredible experiences to help audiences understand that the details make a difference. He also offers valuable insight into the importance of relying on other team members to ensure success in a myriad situations, both personal and professional. Although the nerve injuries Captain Fitch suffered in the crash threatened to end his career, he fought through rehabilitation to resume his work for United Airlines. He is also President of D.E. Fitch & Associates, Ltd., an aviation consulting firm specializing in Cockpit Resource Management and human factors. He received a B.S. degree from Duquesne University and his flight training from the United States Air Force. Captain Denny Fitch is recognized for his extensive experience as a flight instructor and check airman. He also accumulated over 17,000 hours of flight time and is a Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) check pilot designee. http://www.leadingauthorities.com/speakers/speakerDetail.htm?s=3289

|

導演:

拉蒙特強森 (Lamont Johnson)

演員:

卻爾登希斯頓 (Charlton Heston)Captain Al Haynes

理查湯瑪斯 (Richard Thomas) 飾演救難隊長 Gary Brown

詹姆士柯本 (James Coburn) 飾演消防局長Jim Hathaway

DENNY FITCH

AS . Lt. Colonel Dennis Nielsen 中校

湯姆歐布萊恩 (Tom O’Brien) Chris Porter

留言列表

留言列表